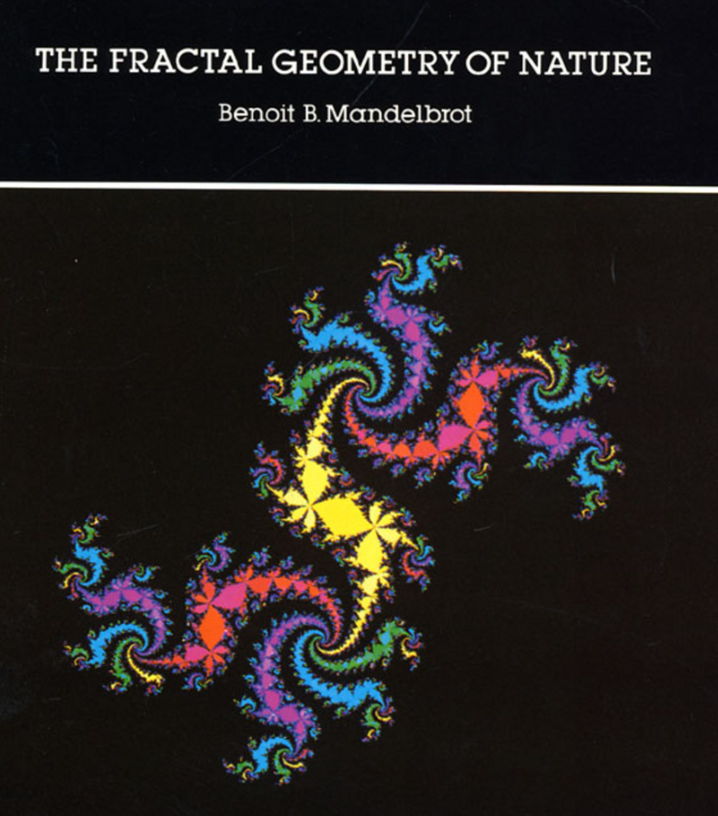

Suggested for readers exploring complexity, scale, and the hidden architecture of natural form.

In this landmark work, Benoit Mandelbrot introduces fractals, mathematical shapes that repeat at every scale, as a new lens for understanding the natural world. From coastlines and clouds to blood vessels and galaxies, Mandelbrot reveals that nature’s patterns are not smooth or simple, but rough, recursive, and self-similar. These forms defy classical geometry, yet they are everywhere.

Mandelbrot’s insight is revolutionary: complexity in nature arises not from randomness, but from iteration. By repeating simple rules across scales, fractals generate forms that are infinitely detailed and structurally coherent. He also proposes that dimensions themselves can emerge through this process, where a line, iterated recursively, becomes a plane, and further iterations yield forms that transcend conventional dimensional categories. These higher dimensions are not just more; they are qualitatively different.

Reading Mandelbrot was a moment of ignition for Fractal Universe. His concept that dimensions emerge through iteration of self-similar forms became a foundational principle in the Fractal Universe framework. The Sparksphere itself is a fractal unit, defined by its qualities of Being and Doing, recursively expressing coherence across nested layers. Like Mandelbrot’s fractals, the Sparksphere metabolizes tension, reorganizes structure, and reveals new dimensional qualities as it evolves.

Mandelbrot’s work also affirmed Gina’s intuitive sense that scale is not just quantitative, it’s qualitative. A shift in scale can reveal new properties, new dynamics, and new forms of meaning. For readers of Fractal Universe, Mandelbrot offers the mathematical mirror to your philosophical scaffolding, a way to see that the universe is not built from static parts, but from living patterns that unfold through resonance and recursion.

“Clouds are not spheres, mountains are not cones, and lightning does not travel in a straight line.” —Benoit Mandelbrot