Most of us grow up assuming that the geometry we learned in school is the geometry of the real world. We picture cubes with perfectly flat faces, spheres with smooth surfaces, and lines that stretch on forever. We also learn to accept a strange mathematical fact: many of the numbers required to describe these shapes—like π—are irrational. They go on forever, never repeating, never resolving into a clean ratio. We treat this as normal, even though it makes the math of physical reality surprisingly messy.

But what if the messiness isn’t in reality at all? What if it’s in the way we’ve chosen to measure it?

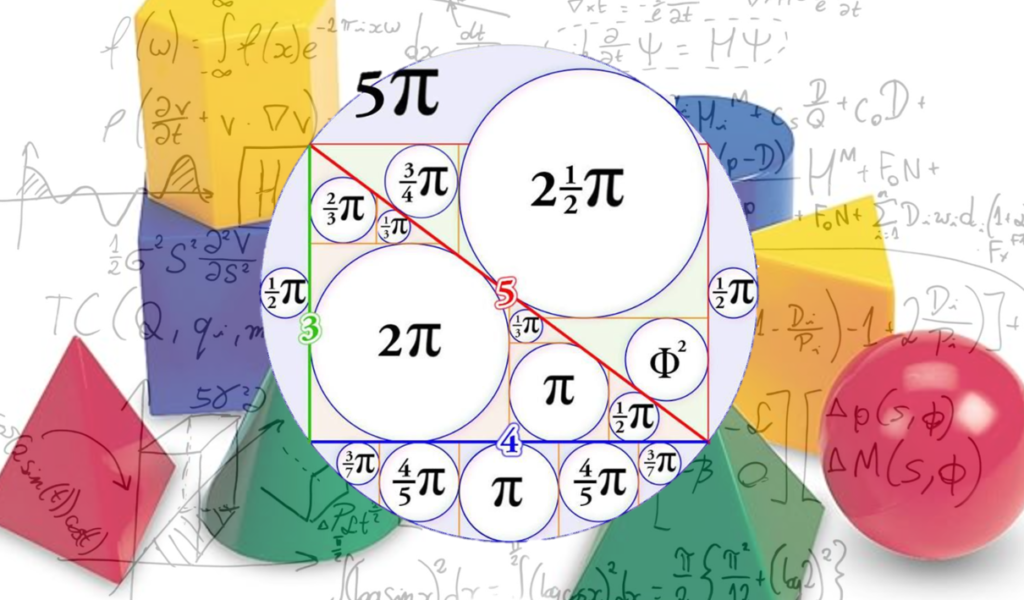

Buckminster Fuller believed exactly that. He argued that the universe itself is built from whole-number relationships, and that the irrational numbers we rely on are artifacts of using traditional geometric assumptions. For example, we imagine solid surfaces everywhere—flat walls, smooth cubes, rigid edges—but no experiment has ever detected a truly solid, continuous surface. At the atomic and energetic levels, everything is open, relational, and in motion. A cube, which depends on perfectly flat faces and perfectly right angles, simply doesn’t exist in nature. It squishes under pressure; it’s not a stable structure.

Fuller proposed that if we want a geometry that matches the physical universe, we should start with the simplest structure that actually can exist: the tetrahedron. Four points, connected by six edges, containing the smallest possible volume. Unlike the cube, the tetrahedron is inherently stable. It doesn’t collapse, wobble, or require imaginary surfaces to hold it together. It’s the minimum “something” that space can form.

By treating the tetrahedron as the basic unit—his “one”—Fuller discovered that many of the relationships in nature become clean, rational, and whole. Instead of relying on irrational constants, the geometry of space becomes countable and relational. In other words, the math begins to behave more like the universe itself.

This shift matters because it reframes how we think about structure, energy, and balance. And it creates a natural bridge to the deeper question at the heart of this post: how do we understand the exact point of balance within all this motion? Fuller approached that question through the Vector Equilibrium, a perfectly symmetrical arrangement of vectors that represents the theoretical zero-state of energy. My own work approaches it through The Stillness, the balance point that appears within every energetic event.

Click below to see a short video about the vector equilibrium:

The Stillness, by contrast, is not a hypothetical precondition but an ongoing feature of reality. It is not a symmetry that collapses the moment energy appears; it is the precise balance point that appears within every energetic event. Where the VE represents a state that cannot persist in the physical universe, The Stillness represents a location that is always present wherever energy is present. It is not the absence of motion but the exact coordinate where forces cancel locally, even as the surrounding system continues to move, oscillate, or transform.

The relationship between Buckminster Fuller’s vector equilibrium (VE) and the concept of The Stillness reveals a subtle but important distinction between geometric idealization and lived energetic reality. Fuller used the VE as a theoretical “zero‑phase” of the universe—a perfectly symmetrical condition in which all vectors are equal and all forces cancel. In this state, no direction is privileged, no dimension has differentiated, and no event has yet occurred. For Fuller, the VE is not something that exists in nature; it is a conceptual limit, a mathematical origin from which asymmetry, motion, and dimensionality emerge the moment equilibrium is disturbed.

This difference reveals two fundamentally different kinds of “zero.” Fuller’s VE is a geometric zero—a perfect, static, unexpressed symmetry that precedes the first event. It is the zero before Becoming. The Stillness is a dynamic zero—a living, relational center that coexists with asymmetry, direction, and change. It is the zero inside Becoming. Fuller’s zero evaporates the moment reality begins to act; The Stillness is the anchor that reality uses to act at all.

Seen this way, the VE becomes a structural metaphor for The Stillness rather than its equivalent. It is the closest geometric analog Fuller could draw, but it remains a boundary condition rather than a lived condition. The Stillness completes what the VE gestures toward: a zero that is not merely theoretical but operative, not merely symmetrical but accessible, not merely prior but immanent. Where the VE describes the idealized womb of geometry, The Stillness describes the living center of experience, physics, and consciousness.